Going too far with Jest Custom Matchers in TypeScript

Dear future me, and other people who land here trying to copy-paste a matcher. Here’s the gist for you.

I needed a Jest custom matcher a few days ago, and I couldn’t find any article I could copy-paste it from. The docs are okay, and they even mention how to use custom matchers in TypeScript, but I think I have some observations which are not included there.

Later down the post I write a lot of unnecessary and overly complex typelevel code, so if you’re a fan of this kind of stuff, bear with me (or press the button below).

Skip to TypeScript shenanigansPor qué?

I wanted to assert that a long string contains a shorter one, disregarding all whitespace and formatting. Something like this:

expect(longString).toContainWithoutWhitespace(shortString);I could write the following

expect(stripWhitespace(longString)).toContain(stripWhitespace(shortString));but then my tests wouldn’t read like prose (lol). I already have a few tests like this and I expect to have a lot more, so I decided to invest in a custom matcher to make my tests more readable.

Here’s how we do this

In reality, I’ve stolen toContain implementation from Jest’s repo and

adapted it a bit, but I’ll go step by step from the ground up, because a

wall of copied code doesn’t help to make a good blog post.

The least we need to do is:

- Write the core logic for our assertion

- Register our matcher with

expect.extend - Merge declarations for our matcher into Jest global types

What would be nice to do:

- Ensure the error messages are friendly and informative to get us started quickly when tests fail

- Validating the input in case our types are disregarded

- Derive the types from the implementation so we don’t have to write things twice. (Mostly because I wanted to have some fun with TypeScript)

The simplest implementation

The smallest thing we can implement looks about like this:

const stripWhitespace = (s: string) => s.replace(/\s/g, "");

const matchers = {

toContainWithoutWhitespace(

// a matcher is a method, it has access to Jest context on `this`

this: jest.MatcherContext,

received: string,

expected: string

) {

return {

pass: stripWhitespace(received).includes(stripWhitespace(expected)),

message: () =>

`Received string "${received}" does ${

this.isNot ? "" : "not "

}contain "${expected}".`,

};

},

};We can import it in our tests and register it with expect.extend.

expect.extend(matchers);Tada! We can now use our matcher 🎉 There’s a small problem though.

TypeScript doesn’t know about it, so our tests are all red and fiery. Time

to merge our function into jest.Matchers type.

// Hey TypeScript, let's go to global scope.

declare global {

// Where `jest` namespace is already defined. Let's go inside it.

namespace jest {

// Remember the Matchers interface that was already defined here?

interface Matchers<R> {

// This interface contains one more method now! Cool, huh?

toContainWithoutWhitespace(substring: string): R;

}

}

}You can read more on merging interfaces, merging namespaces, and global augmentation in TypeScript docs.

Let’s see how our matcher works.

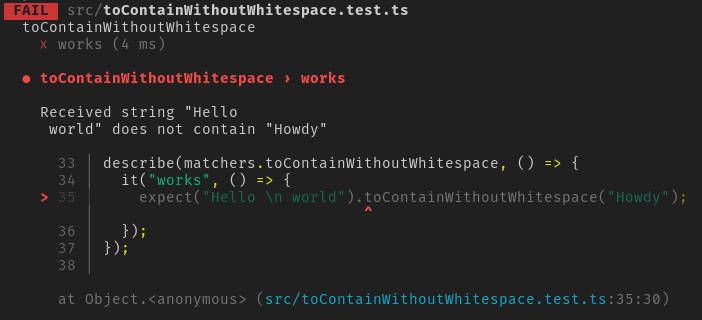

Expand text from the picture 👈

FAIL src/toContainWithoutWhitespace.test.ts

toContainWithoutWhitespace

✕ works (5 ms)

● toContainWithoutWhitespace › works

Received string "Hello

world" does not contain "Howdy"

33 | describe(matchers.toContainWithoutWhitespace, () => {

34 | it("works", () => {

> 35 | expect("Hello \n world").toContainWithoutWhitespace("Howdy");

| ^

36 | });

37 | });

38 |

at Object.<anonymous> (src/toContainWithoutWhitespace.test.ts:35:30)The output doesn’t look bad, but our matcher is definitely less cool than the built-ins.

Minor Improvements

Let’s improve the message formatting and add some color to it. We’ll grab some useful functions from jest-matcher-utils.

import { printExpected, printReceived } from "jest-matcher-utils";printExpected and printReceived color their arguments with green and red

respectively.

import { getLabelPrinter } from "jest-matcher-utils";

const printLabel = getLabelPrinter(labelExpected, labelReceived);getLabelPrinter measures its arguments and returns a function appending

spaces to align our output into neat columns.

import {

MatcherHintOptions,

matcherHint

}matcherHint gives us a string that should look like the failing line from

our test, including modifiers like .not.

It’s best illustrated by an example.

const matcherName = "toContainWithoutWhitespace";

const _1 = matcherHint(matcherName, "text", "substring");

// const _1 = "expect(text).toContainWithoutWhitespace(substring);"

const _2 = matcherHint(matcherName, "text", "substring", {

isNot: true,

promise: "resolves",

});

// const _2 = "expect(text).resolves.not.toContainWithoutWhitespace(substring);"isNot and promise are slots

for this.isNot boolean

and this.promise "rejects" | "resolves" | ""

from Jest matcher context.

We can also add a comment and customize colors of first and second arguments (“text” and “substring” in our exmmple)

import * as chalk from "chalk";

const _2 = matcherHint(matcherName, "text", "substring", {

isNot: this.isNot,

promise: this.promise,

comment: "\(`0´)/",

expectedColor: chalk.bgMagenta.bold,

receivedColor: chalk.blue.italic.inverse,

});We could go mad with it, but uhh… please don’t?

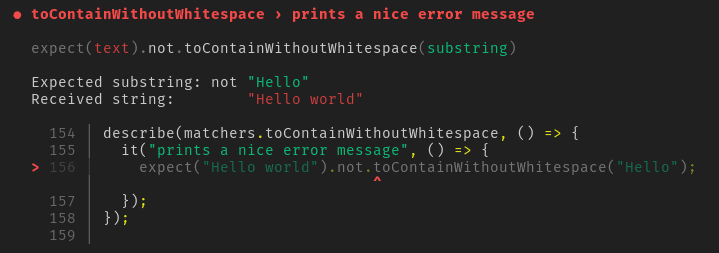

Expand text from the picture 👈

expect(text).not.toContainWithoutWhitespace(substring) // \(`0´)/Let’s see how our matcher would look like with all of these:

const matchers = {

toContainWithoutWhitespace(

this: jest.MatcherContext,

received: string,

expected: string

) {

const pass = stripWhitespace(received).includes(

stripWhitespace(expected)

);

const message = () => {

const labelExpected = "Expected substring";

const labelReceived = "Received string";

const printLabel = getLabelPrinter(labelExpected, labelReceived);

const matcherName = "toContainWithoutWhitespace";

const isNot = this.isNot;

const matcherHintOptions: MatcherHintOptions = {

isNot,

promise: this.promise,

};

const hint =

matcherHint(matcherName, "text", "substring", matcherHintOptions) +

"\n\n";

return (

hint +

printLabel(labelExpected) +

(isNot ? "not " : " ") +

printExpected(expected) +

"\n" +

printLabel(labelReceived) +

(isNot ? " " : " ") +

printReceived(received)

);

};

return { message, pass };

},

};

Expand to read the message. 👈

● toContainWithoutWhitespace › prints a nice error message

expect(text).not.toContainWithoutWhitespace(substring)

Expected substring: not "Hello"

Received string: "Hello world"

110 | describe(matchers.toContainWithoutWhitespace, () => {

111 | it("prints a nice error message", () => {

> 112 | expect("Hello world").not.toContainWithoutWhitespace("Hello");

| ^

113 | });

114 | });

115 |Way nicer than before, innit?

Runtime validation

When we call expect.extend our matcher is added to all expectations, even

the ones not on strings (not for long!), so we need to

validate the input.

We’ll grab some more utils from jest-matcher-utils and use them to build

import {

EXPECTED_COLOR,

RECEIVED_COLOR,

matcherErrorMessage,

printExpected,

printReceived,

printWithType,

} from "jest-matcher-utils";

const matchers = {

toContainWithoutWhitespace(

this: jest.MatcherContext,

// We use `unknown` here, because we're not guaranteed to receive strings

received: unknown,

expected: unknown

) {

const matcherName = "toContainWithoutWhitespace";

const options: MatcherHintOptions = {

isNot: this.isNot,

promise: this.promise,

};

if (typeof received !== "string") {

throw new Error(

matcherErrorMessage(

matcherHint(

matcherName,

String(received),

String(expected),

options

),

`${RECEIVED_COLOR("received")} value must be a string`,

printWithType("Expected", expected, printExpected) +

"\n" +

printWithType("Received", received, printReceived)

)

);

}

if (typeof expected !== "string") {

throw new Error(

matcherErrorMessage(

matcherHint(matcherName, received, String(expected), options),

`${EXPECTED_COLOR("expected")} value must be a string`,

printWithType("Expected", expected, printExpected) +

"\n" +

printWithType("Received", received, printReceived)

)

);

}

// redacted for brevity

},

};

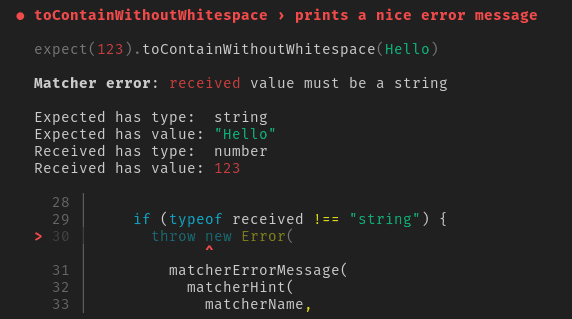

Expand to read the message. 👈

● toContainWithoutWhitespace › prints a nice error message

expect(123).toContainWithoutWhitespace(Hello)

Matcher error: received value must be a string

Expected has type: string

Expected has value: "Hello"

Received has type: number

Received has value: 123

28 |

29 | if (typeof received !== "string") {

> 30 | throw new Error(

| ^

31 | matcherErrorMessage(

32 | matcherHint(

33 | matcherName,Sweet error message. We’ll instantly know what went wrong and where.

Our matcher is now in its final form, and since it’s destined to be

registered with expect.extend we can go one step further to minimize our

API surface and the number of lines users have to write. Instead of

exporting our matchers, we’ll register them ourselves.

const jestExpect = (global as any).expect;

if (jestExpect !== undefined) {

jestExpect.extend(matchers);

} else {

console.error("Couldn't find Jest's global expect.");

}Now anybody can get toContainWithoutWhitespace just with a side-effect

import.

import "./our-matchers";Type-level shenanigans

We have arrived to the fun stuff.

Remember that runtime validation few paragraphs above? Right now we could

use this after any expect(actual), but our implementation throws for

anything that’s not a string. This is an inconvenience.

Let’s add a simple conditional type to fix it. In tests written in

TypeScript, we’ll prevent from using our matcher if the argument passed to

expect is not a string.

Fortunately, Matchers interface provides us with T parameter with the

type of value given to expect.

declare global {

namespace jest {

interface Matchers<R, T = {}> {

toContainWithoutWhitespace: T extends string

? (substring: string) => R

: "Type-level Error: Received value must be string";

}

}

}This way, we can always check that toContainWithoutWhitespace exists, but

we can call it only when the tested value (the T we get from Jest’s types)

is a string.

This typelevel X extends Y ? A : B is a

conditional type.

You can read extends as is assignable to and then it works like usual

inline if.

Our implementation uses unknown and validates its arguments so we’re

covered from both sides.

Okay, but what if I have a production codebase, an a ton of custom matchers — imagine a big number like ℵ0 or 8?

Going too far with types

( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)

Insted of writing signatures of our matchers to add them to Matchers

interface, we can compute them from the implementation!

/// <reference types="@types/jest" />

const matchers = {

toHaveWordsCount(

this: jest.MatcherContext,

sentence: string,

wordsCount: number

) {

// implementation redacted

},

};Okay, what information do we have here?

- The function name is important, obviously.

- We’re not interested in

this: jest.MatcherContext. sentenceis passed toexpect, and we wanttoHaveWordsCountto appear only if the sentence is a string.wordsCount: numberwill be the only argument of the function we’re trying to derive.

So what do we need?

Certainly, we need something extract function arguments. — Parameters is a

built-in.

// type _Step1 = [sentence: string, wordsCount: number]

type _Step1 = Parameters<typeof matchers.toHaveWordsCount>;We need something to get rid of that sentence. We could have more

arguments, so we’re not interested in picking the second one, but in

skipping the first. A function which does it is usually called tail.

type Tail<T extends unknown[]> = T extends [infer _Head, ...infer Tail]

? Tail

: never;

// type _Step2 = [wordsCount: number]

type _Step2 = Tail<_Step1>;We can combine it into something like this.

// type _Step3 = { toHaveWordsCount: (wordsCount: number) => void; }

type _Step3 = {

toHaveWordsCount: (

...args: Tail<Parameters<typeof matchers.toHaveWordsCount>>

) => void;

};We’ll have to

map over

typeof matchers instead of listing its properties one by one.

type OurMatchers = typeof matchers;

// type _Step4 = { toHaveWordsCount: (wordsCount: number) => void; }

type _Step4 = {

[P in keyof OurMatchers]: (

...args: Tail<Parameters<OurMatchers[P]>>

) => void;

};And turn it into a generic type parametrized by the type of our matchers implementation.

type GetMatchersType<TMatchers> = {

[P in keyof TMatchers]: (...args: Tail<Parameters<TMatchers[P]>>) => void;

};Okay, this doesn’t quite work yet — we’ve got an error.

Type

TMatchers[P]does not satisfy the constraint(...args: any) => any.

Parameters is defined like this:

type Parameters<T extends (...args: any) => any> = T extends (

...args: infer P

) => any

? P

: never;Noticed this generic constraint? We can’t use Parameters on something that

isn’t a function. Of course!

type AnyFunction = (...args: any) => any;

type GetMatchersType<TMatchers> = {

// for each property in TMatchers

[P in keyof TMatchers]: TMatchers[P] extends AnyFunction

? // if it's a function we transform it like we wanted

(...args: Tail<Parameters<TMatchers[P]>>) => void

: // if it's not a function, we have no beef with it — we pass it further

TMatchers[P];

};We’re almost done. but do you remember that R parameter Matchers

interface had? It holds the return type of the matcher. If I’m not wrong it

has something to do with Jest’s .resolves and

.rejects which turn the

result of matchers after them into a promise. For our use case, let’s just

play nice and pass it along because all the builtin matchers do.

interface Matchers<R, T = {}>

toBeDefined(): R;

toBeFalsy(): R;

toBeGreaterThan(expected: number | bigint): R;

// ...redacted for brevity

}See?

Here goes our final GetMatchersType.

type GetMatchersType<TMatchers, TResult> = {

[P in keyof TMatchers]: TMatchers[P] extends AnyFunction

? (...args: Tail<Parameters<TMatchers[P]>>) => TResult

: TMatchers[P];

};The only thing left to do is ensuring that toHaveWordsCount appears only

if the value given to expect is a string.

type FirstParam<T extends AnyFunction> = Parameters<T>[0]

type OnlyMethodsWhereFirstArgIsOfType<

TObject,

TWantedFirstArg

> = {

[P in keyof TObject]: TObject[P] extends AnyFunction

? TWantedFirstArg extends FirstParam<TObject[P]>

? TObject[P]

: [`Type-level Error: this function is present only when received is:`, FirstParam<TObject[P]>]

: TObject[P]

}Let’s try it out:

type OurMatchers = {

toHaveWordsCount(sentence: string, wordsCount: number): void;

toBeGreaterThan(actual: number | bigint, expected: number | bigint): void;

};

// type _Step6 = {

// toHaveWordsCount: ["Type-level: this function is present only when received is:", string];

// toBeGreaterThan: (actual: number | bigint, expected: number | bigint) => void;

// }

type _Step6 = OnlyMethodsWhereFirstArgIsOfType<OurMatchers, number>;I went with that fake type-level error because it carries more information

than never. There is a

nice draft PR to

TypeScript repo implementing throw-types, but faking it with strings and

arrays is the best of what we have today.

Here’s how it looks like in practice.

// 🔥 This expression is not callable.

// Type '["Error: this function is present only when received is:", string]' has no call signatures.(2349)

_step6.toHaveWordsCount(2);A bit messy, right? I’ll argue it’s still better than never carrying no

information.

Going back to Jest, we’re ready to merge into jest.Matchers and use our

new matchers!

declare global {

namespace jest {

interface Matchers<R, T = {}>

extends GetMatchersType<

OnlyMethodsWhereFirstArgIsOfType<typeof matchers, T>,

R

> {}

}

}

// ✅

expect("foo bar").toHaveWordsCount(2);

// 🔥 error as expected

expect(20).toHaveWordsCount(2);Have a play with it in TypeScript Playground.

Let me know if you liked this post. Thanks for reading!